Eliminating Nonessential Overhead

Or, why receipts probably don’t matter…

Managing a business means dividing your time between management and business. Every organization has a core function at which it excels, and an array of secondary functions required to keep things running smoothly. The best businesses are those that keep the secondary work under control while focusing as completely as possible on the primary tasks.

Easier said than done.

Most of us in the startup world started our careers at established companies, where there were well defined processes to handle the overhead of daily operations. Rigid systems are a great way to learn rigor, they create an external pressure to perform while leaving no room for subjectivity. Habits formed “because they’re company policy” unlock opportunities we never would have anticipated; we learn the value of detailed call notes or well-commented code.

But rigidity is confining and inefficient, and not all policy is effective. Many founders leave their corporate jobs to start their own businesses precisely because they recognize just how unnecessary many of those TPS reports and 7AM all-hands meetings are. They start new businesses and vow to focus only on what matters.

Yet we still see so many founding teams wasting time on completely nonessential work, despite (and ironically, because of) their eagerness to shed these corporate roots.

Three Types of Activity

To cut to the heart of this problem, I’m going to vastly oversimplify business activity into three categories. We can think of anything we spend our time or money on as falling into one of these buckets.

At the heart of our business is the core activity, this is what you do better than anyone else; all the work you’re doing to develop your product or grow your practice. If you had your way, this would be all you ever spent your time on.

Alas, next up comes the essential overhead. This is the stuff you can’t avoid, the crucial support work needed to keep the business running effectively and the employees happy. Think sending invoices, paying utilities, recruiting new team members, and filing taxes. You can avoid this stuff for a while to focus on the core (and many founders do), but it will always catch up to you in the end if you want to get paid for your work and have a working internet connection.

Finally, there’s nonessential overhead. Here’s anything that isn’t directly related to your core mission, and which also doesn’t effectively support the organization. These practices and expenses slowly creep into any business as it grows and tries out new things, effective management means proactively weeding out the useless stuff and keeping what works.

Needs evolve as a business grows. New companies are almost entirely focused on their core business and can only afford distractions that are 100% necessary to keep the lights on. As a business grows, the team gets larger, contracts become more complicated, systems become more formalized and workers specialize more. Essential overhead grows to manage those complexities, making core work more focused and efficient, even as it occupies a smaller portion of overall time and money spent.

A growing team tolerates some nonessential overhead as the price of trying new things but is careful to abandon anything that isn’t effective. On the other hand, businesses die when they lose sight of what’s truly critical, letting those superfluous processes accumulate while the core business loses focus.

Life Without a Back Office

An important distinction here is that what’s essential for one business may be nonessential for another, depending on any number of factors, size being one of the most important. This gotcha causes many businesses with corporate roots to create new inessential processes even as they so eagerly discard old ones.

Here’s an example we see often: you’ve spent years building your career within a big organization, becoming a master of your craft. That mastery allows you to view your organization’s culture with a critical eye, so you start your own business with a fresh approach and less overhead.

The business gains traction, but now you are dealing with investors, lawyers, payroll providers, and the IRS – things you had other departments to handle in the corporate world. You’ve got no mastery in these areas, so you fall back on what you know: photographing receipts, filling out timesheets, and subjecting every document to legal scrutiny.

Here’s the thing, for a 5,000 person company, each of those things is essential. The company has a complicated stack of departments and sub-departments, different legal entities or bank accounts, and may have regulatory reasons for document retention. Even small legal matters can be huge liabilities.

But for a company of 5, you can make do with much less. You just might not know that.

As a general rule, small businesses are far more efficient at their founders’ strengths, but can be far less efficient at supporting functions. Understanding whether a task or process is essential or not sometimes requires expertise. And that expertise may not exist within your organization.

What Creates Nonessential Overhead?

Nobody sets out to create useless meetings or busy work. Management is hard because we usually don’t have perfect information about what works and what doesn’t. If we do, it’s because we’re spending time gathering that information. The limitation of any framework for defining tasks (like the Eisenhower Matrix) is that simply classifying the tasks can be a full time job.

Process gives us comfort, even when it doesn’t work. That weekly all-hands isn’t just a chance for the CEO to hear themselves talk; it’s making them feel like something is being done about the growing team losing cohesion. And that stack of receipts in your drawer gives you comfort that even though you haven’t spoken to an accountant yet, you’re at least doing your part as a good corporate citizen.

Finance, accounting, tax, and compliance are littered with situations like this, because those functions are essential to everyone and core to almost nobody. Without the necessary expertise, how can you possibly define a lean but effective financial, legal, or tax process? Most wind up wasting too much time on processes that still end up disorganized.

Here’s the thing, if you’re not an experienced CPA you shouldn’t be telling your accountants what to do, at least not exclusively. They should also be telling you what needs doing. The fact that small businesses are stricken with burdensome overhead, and that so many founders spend time learning entirely new skillsets just to manage it, means that their accounting, legal and financial partners aren’t being sufficiently proactive.

Why is this Important?

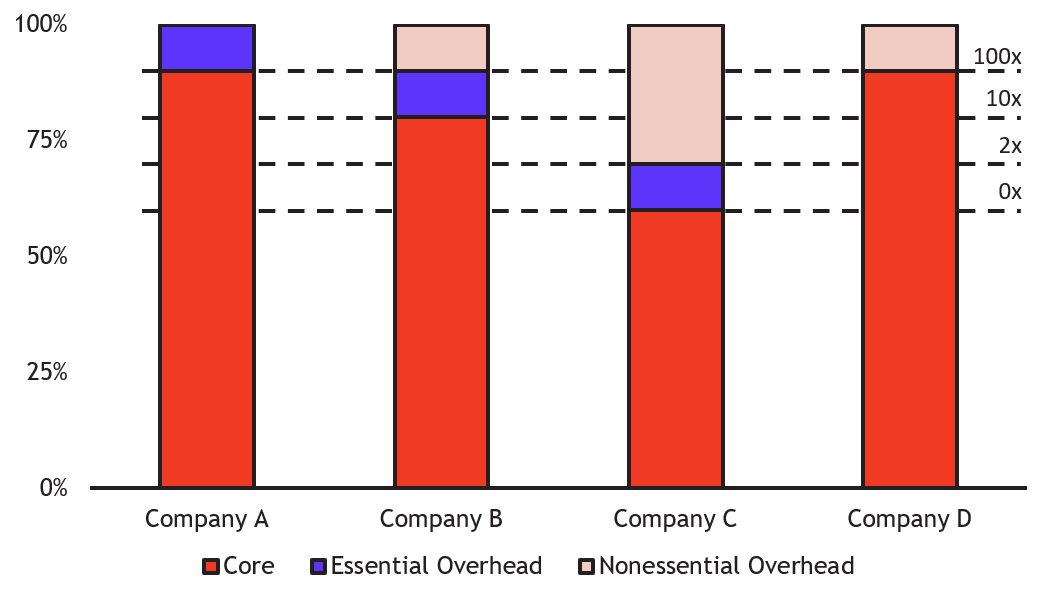

Small business leaders need to be thoughtful about seeking proactive partners. In the startup world margins are small and every decision can be a high-leverage one. If your business has 100x growth potential, every dollar wasted now costs you $100 down the road. And the business wasting lots of dollars isn’t usually the one that hits that 100x target.

The difference between Company A and Company B isn’t huge, but what could you do with more time to focus on your business? In most industries, the margin between good and great is much smaller than the 10% that my made-up numbers suggest.

And as a matter of confidence, the difference is huge. Company A runs a business based on informed essentialism. Company B does alright, but without better advice they worry that they’re actually more like Company C (whose bar trivia and kickball teams far outperform their business) or Company D (who crushes the competition before being crushed by the IRS).

There’s real value at stake when businesses fail to audit their overhead with the same attention they pay to their core business. Your lawyer may not want to tell you when not to consult a lawyer, your accountant may not want to automate data collection to reduce their billable hours. It’s always easier for them to do what they’re told than to actively advise you. But if you’re not asking these questions, you won’t find the people with the answers.

This article was written by Ben Coleman and can also be read here.